私たちは、西洋を中心とする建築の歴史を研究する研究室です。建築史研究は、知的刺激に満ちあふれた学問であり、建築の魅力を解き明かす重要な分野であると、私たちは考えています。

歴史上の魅力溢れる建築の数々を真摯な姿勢で研究することが、ひいては現代建築、さらには未来の建築を解き明かす建築理論を構築することにつながると、私たちは考えています。

加藤研究室では、たとえば以下のような観点から建築史の研究をおこなっています。

- 物質と構築がつむぐ建築史

構法・材料・構造といった具体的なモノとしての建築に着目しながら、単なる技術論にとどまるのではなく、空間論、建築理論まで発展させる研究方法として。K.フランプトン『テクトニック・カルチャー』以降の建築史学のあり方。

時間変化にさらされる「物質(モノ)」としての建築と、時間をこえて生き続ける「建てる技芸」としての建築。ふたつの視点から西洋建築の歴史をとらえなおし、スクラップ&ビルドありきの建築観を脱して真に豊かな建築文化のありかを示す。『時がつくる建築』のさらに先へ――。

【本書「はじめに」より】

本書『建築のラグジュアリー』の出発点にあたる体験を、はじめにお話ししたい。本書は、高級品について論じるわけではない。人びとが建築を、さらに建築以外のモノを、愛着を持って長く使い続けることの価値を「ラグジュアリー」と捉え、私たちの身のまわりの建築とラグジュアリーを再び繫ぎ直すことが、本書の目的である。

「構築術的空間論としてのゴシック建築研究」

(『ゴシック様式成立史論』序章)

「アーキテクトニックな建築論を目指して」

(連載)(10+1 website)

- 近代建築史の再考

21世紀の現在、20世紀における建築学の常識が、多くの場面で常識として通用しなくなり、建築の現場ではさまざまな新しい試みが登場している。建築史学の分野が成すべきは、近代的建築観を一歩引いた視点から歴史的に位置付け直すことだろう。

『近代建築理論全史 1673-1968』ハリー・フランシス・マルグレイヴ 著、加藤 耕一監訳、丸善出版、2016年

- 建築時間論

建築を竣工年代によってカタログ化(点の建築史)するのではなく、建築が時間の変遷とともにどのような変化を遂げていったのか(線の建築史)という点に着目する。「建築」:「建築家」:「竣工年」を一対一対応させがちな、近代的建築観からの脱却。

(東大出版会、2017年)

ex. 「建築時間論──近代の500年、マテリアルの5億年」

(10+1 WEBSITE「特集 時間のなかの建築、時間がつくる建築」2017年6月)

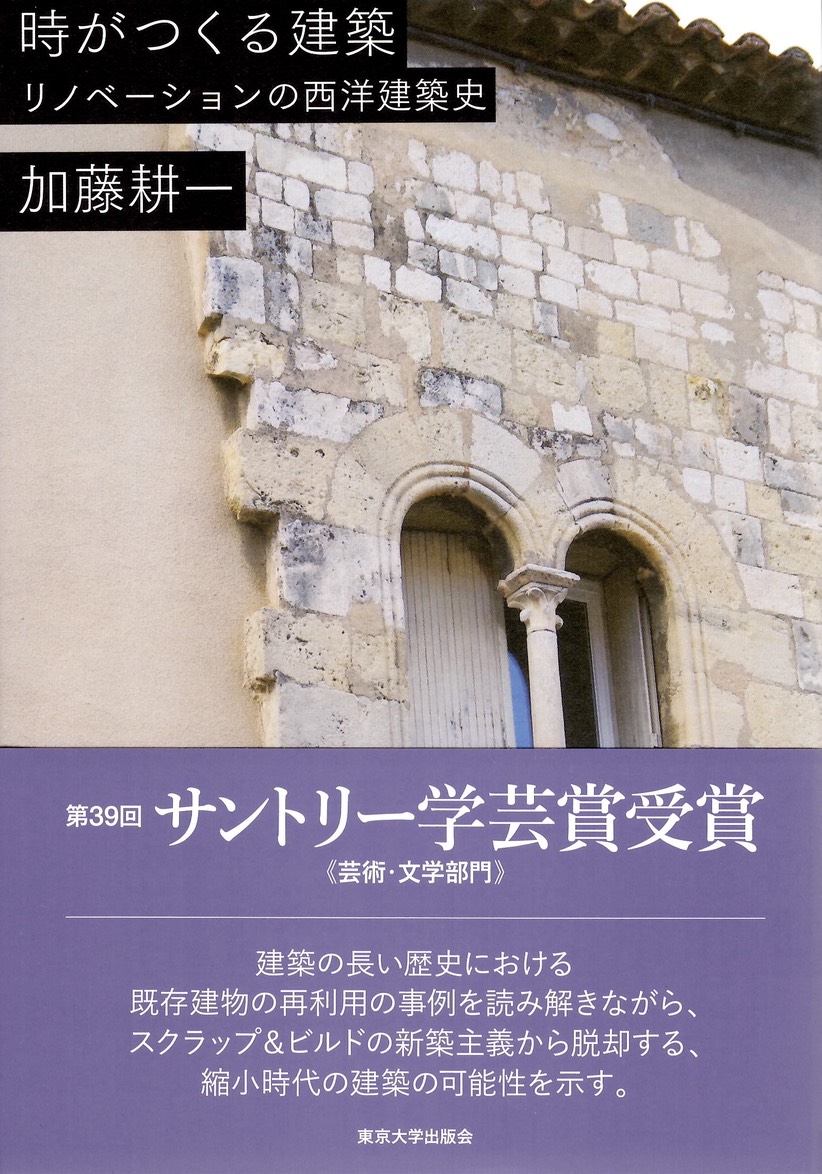

時がつくる建築

リノべーションの西洋建築史

Architecture in Time:

Survival of buildings through history and social change

加藤 耕一

内容紹介

建築の長い歴史からみれば,既存建築の再利用(リノべーション)はきわめて重要な建築的創造行為であった.西洋建築史にみられる数々の既存建物の再利用の事例や言説を読み解きながら,スクラップ&ビルドの新築主義から脱却し,より豊かな建築とのつきあいかたを示す.

Architecture in Time:

Survival of Buildings through History and Social Change

Introduction (Translation from Japanese)

Architecture is not "Bulky Garbage"

The premise of this book is the question of whether the era of modernity is drawing to a close, and whether we are standing in a transitional period between modernity and the next era. The modern era referred to here is simply the "growth era" of modernity.

From a broad perspective, the "current" era is a historical turning point from an era of growth to an era of contraction. Of course, there are still some regions globally, such as parts of Asia and Africa, that are in the midst of growth. However, as the metaphor of "growth" and "maturity" suggests, mature "adults" will only develop their girth if they continue to desire physical "growth".

In this age of shrinking populations, we are faced with declining populations, aging populations, shrinking cities, the hollowing out of suburbs and regional cities, and the problem of vacant houses. These are problems that have opposite vectors to those faced by modern architecture.

The problems are the opposite side of the spectrum from those faced by architecture in the modern era. In the midst of the growth era, the population explosion and urban sprawl were problems, and after the two world wars, the massive supply of housing became a problem throughout the world. Modernism, the architecture of the first half of the 20th century, emerged to solve these problems, and in the second half of the century, architectural responses to the ever-growing cities became an even more important theme.

The methodologies that have solved architectural and urban problems in the 20th century may still be effective if brought to Southeast Asia and Africa. But what about Japan? Will the continuation of 20th century methodology make us happy?

Comparing Japan with Europe and the U.S., both of which are in the same "maturation period," it seems that the Japanese view of architecture is extremely heterogeneous. For example, when a Japanese house is paid off after 35 years of mortgage payment, it is not worth the total amount paid for it. The asset value of a 35-year-old house is surprisingly low. If one were to sell the land on which the house stands, the cost of demolishing the old house would be high, so it would be more expensive to sell the house after clearing the land. The houses are almost always treated as bulky trash. In addition, the percentage of vacant houses in Japan exceeded 10% around 2000 and continues to increase. Nowadays, these vacant houses are being considered as troublesome oversized garbage and how they should be removed is being discussed.

In Europe and the U.S., however, it seems that the amount of investment in housing often corresponds to the amount of assets. In other words, in Europe and the U.S., old houses are not considered bulky waste. On the contrary, used houses are sold on the real estate market as valuable assets that are worth the amount invested. A real estate agent I met in Paris when I was studying abroad said, "You can sell an apartment in Paris for the same price you paid for it. Unfortunately, he was selling to the wrong person.

Where does the difference between Westerners' and Japanese people's perception of used houses come from? Is it because the Japanese have a traditional and cultural belief in new construction that cannot be changed? It is true that Japan is home to the ISE-JINGU Shrine. The shrine is famous for the SHIKINEN-SENGU, a ceremony held every 20 years to welcome the gods to the newly built, shiny new shrine pavilions, and is the embodiment of Japanese tradition. On the other hand, there is also HORYU-JI Temple in Japan. It is the oldest wooden structure in the world, and has been standing for more than 1300 years, replacing damaged parts. Japan must also have had a cultural tradition of appreciating the old, such as WABI-SABI. Even if Japanese traditional wooden architecture seems to have a shorter life span than Western traditional stone architecture, we should be more proud of the oldest wooden architecture in the world.

One might hear a nasty retort that HORYU-JI Temple has been so repeatedly replaced over the years that there is hardly any 1300-year-old wood left in the temple. However, even in masonry construction, broken or chipped stones are often replaced and repaired, although this is less common than in wooden construction. The difference between wood and stone construction is a matter of degree, not a fundamental difference.

This book is an attempt to challenge this Japanese view of architecture and values. The value system of abandoning the old and seeking the new must have been an unusual value system peculiar to 20th century Japan. Of course, the Japanese people are not the only ones who feel pleasure in new things. However, the difference between the Japanese sense of "I am ashamed of my old house" and the Western sense that old houses fetch high prices in the real estate market reveals a hierarchy of values between the old and the new that lies subconsciously in the Japanese mind. In other words, there is an assumption that the new is good and the old is evil.

This is probably a value shared by many Japanese. And when they learn that old houses are actually sold at high prices in Europe and the United States, they probably say, "Japanese buildings are different from Western buildings. However, most of the buildings built before Japan's westernization, before the Meiji period, are already cultural assets, and are not subject to the real estate sales discussed here. The difference is not the architecture itself, but the value. What is different is not the architecture itself, but the values. And those values are probably not even traditional Japanese values. I would like to call them "20th century values. What we should aim for is to break away from the 20th century values.

Architectural Renovation, Architectural Reuse

The central theme of this publication is the reuse of existing buildings. As a response to the economic stagnation since the end of the 20th century, the term "renovation" has often been heard in Japan. To the general public, "renovation" still sounds like an technical term, but in fact it is a term commonly used by people in Europe and the United States to refer to the process of modifying old things. In Japan, too, "renovation" has become a common noun in the architectural world. However, even in the architectural world, renovation as a job is still seen as a completely different and lower level of work than new construction. In other words, renovation is nothing more than a niche market that has come into vogue in response to recent economic conditions.

But is this really the case? What this book aims to show is that in the long history of architecture, the reuse of existing buildings has also been an essential architectural activity, and that the value system in which the scrap-and-build principle of new construction is seen as superior to renovation is merely a fad of the last century, brought about by the 20th century view of architecture. The hypothesis is that the values that make scrap-and-build new constructionism appear superior to renovation are merely a first-century fad brought about by the 20th century view of architecture. As this book reveals, the history of Western architecture is replete with examples of the reuse of existing buildings. However, until now, little attention has been paid to them. This is because it is an issue that is not necessary in the context of 20th century values. Rather, the study of architectural history has focused on how historical architects created new architecture. However, historical architects apparently wielded their abilities in both new construction and renovation as important acts of architectural creation. Perhaps people in the West take this history for granted. Another aspect of architecture is the reuse of old buildings and their rebirth as modern structures.

On the other hand, Japan's shift from the traditional world of "carpentry" and "buildings" to the Western world of "architects" and "architectural works" has been extremely short-lived. However, the shift has been a thorough one, and over the past century, Japanese people have solidified their "20th century view of architecture. We Japanese know little about the history of the reuse of existing buildings in the West.

We Japanese know little about the history of reuse of existing buildings in the West, and we feel that modern society is disconnected from the history of traditional Japanese wooden buildings, which have repeatedly reused components. They think of architecture as new construction, and feel ashamed to continue to use old buildings. Although there are more and more examples of attractive revitalization of old buildings in the world these days, people think that these are only special cases that occur in a few cultural places, and have nothing to do with our homes. Once again, the sense that "the West is different from Japan" has appeared. Isn't it unfortunate that we continue to lock ourselves in a cage of preconceived notions and yet establish a strict hierarchy between new construction and renovation?

My specialty is the history of Western architecture, so I cannot discuss the history of reuse in traditional Japanese architecture. However, I have a vague hope that if we can break free from the "20th century view of architecture" by first learning about the history of reuse in Western architecture, we can move on to the next step.